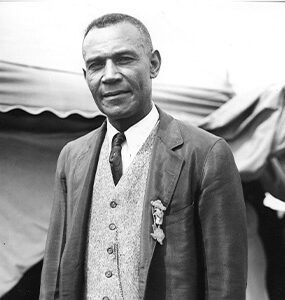

Bio

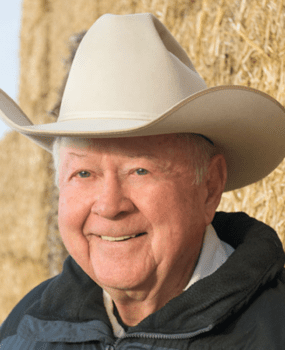

Cowboy and Civic Jeader

Mathew (Bones) Hooks, cowboy and horse breaker, was born on November 3, 1867, to parents Alex and Annie (who took their former slave master’s last name Hooks) in Robertson County, Texas. At age seven he began work as the driver of a butcher’s meat wagon, and at nine he began driving a chuck wagon for Steve Donald, who used the DSD brand. The next year he learned to ride a horse at his home in Henrietta, Texas. At the age of nine, he drove a camp wagon pulled by two old steers, Buck, and Berry, to D. Steve McDonald’s DSD ranch in Denton County. Hooks became one of the first black cowboys to work alongside Whites as a ranch hand. He remained with Donald until adulthood and then joined J. R. Norris’s ranch on the Pecos River. With Norris he made many trail drives from the Pecos country, doing something unheard of in those times, raised horses in partnership with a White man! and became a top horse breaker. Hooks later recounted that cowboy in the Pecos River country kept bringing him wild horses as a challenge, until they finally realized there was none he could not ride.

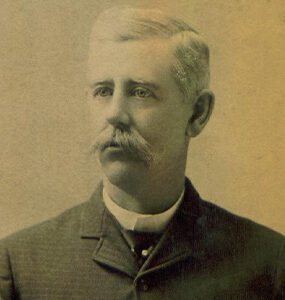

When J.R. Morris, a cattleman from the JRE ranch on the Pecos, visited the DSD, it intrigued him to see that Bones worked harder than most of the grown men on the ranch. Norris said to the barefoot youth, “I’ll buy you a pair of boots and make a real cowboy out of you if you come to work at my place on the Pecos.”

Bones eagerly accepted Norris’ offer and began his career as a horse trainer on the isolated JRE ranch. He took part in many trail drives to Kansas before 1886 – his 19th year – when he helped to bring a herd to the young Texas town of Clarendon.

As the only black man in sight, Bones was very lonely in the Panhandle, but he loved the prairie country and the orderly community and was determined to remain there. He stayed in and near Clarendon for the next 23 years and made a name for himself as the top horse wrangler in that part of the country.

Religion was very important to Bones, and he was instrumental in founding and building at Clarendon the first black church in the Panhandle. Bones never used tobacco or alcohol although it was said that he bet on horses occasionally.

Bones associated with many of the early day Panhandle ranchers. J.S. Wynne, an expert horse trainer, helped Bones perfect his skill of managing horses. On the Bar CC ranch, located on Home Ranch Creek, Bones was befriended by Dave Lard who had many fights with new hands for teasing Bones. The black cowboy said that he was an “Angus” among “White Faces.”

When cattleman Tom Clayton died in the early 1890s, Bones took a bunch of white wildflowers to the funeral. This was the beginning of a tradition with Bones, who afterward would send a single white flower to the funeral of every pioneer he knew. Later the tradition included living persons who he felt had accomplished something noteworthy. In addition to area citizens Bones sent white flowers to several United States presidents, world leaders and religious notables. Among these were President and Mrs. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Will Rogers and Sir Winston Churchill.

The written acknowledgements sent to Bones by hundreds of persons who had received his white flowers were kept together in a leather bag – his most “prized possession” these acknowledgements are housed in the Amarillo Public Library.

In May, 1909, Bones left the range to work as a porter for the Santa Fe Railway. In the summer of 1910, he was working in a day coach when he overheard four men talking about horses. Bones said later, “I sort of hung around, dusting the seats, because I don’t like to miss any horse talk.”

The men were talking about “Old Bob,” a black mustang owned by Moore Davidson of Pampa. It was said that nobody could ride that horse, but Bones broke in and told the men, “I can ride that horse.”

The men were amused when Bones told them to telegraph Davidson and ask him to have the horse at the depot when the train was scheduled to reach Pampa. This was arranged and it was agreed that Bones would receive $25 if he succeeded in riding the horse.

Bones had broken horses for J. Frank Meers when Meers was the foreman on the Masterson ranch. Meers was one of the men who brought “Old Bob,” the “unrideable” black mustang from Davidson’s place south of Pampa to the place where a large crowd had gathered south of the depot. Lewis F. Meers, son of J. Frank, played “hooky” from school to watch the event.

The train arrived at the Pampa depot about 2 a.m. Bones, booted and spurred and minus his white porter’s jacket, descended from the train. He is reported to have said later, “I combed that bronc from his ears to his tail, rode him to a standstill, collected my money, and was back on the train when it pulled out seven minutes later.”

Bones moved to Amarillo about 1911 and remained there most of the rest of his life. He married Anna Crenshaw who died in the early 1920s. They had no children.

Bones retired from the railroad in April, 1930, and thereafter devoted his time to civic affairs. Soon he became recognized as a leader who worked unceasingly for the betterment of his people. He was the first black man to sit on the Potter County Grand Jury and the first of his race to be a member of the XIT Association, the Montana Cowpunchers Association, the Western Cowpunchers and the Pampa Old Settlers Association.