Introduction

Beginning in the 1830s and continuing into the 1890s, the United States Army acted as the federal government’s principal agent of expansion into the western frontier. One historian writes, “At any given time during this period, fewer than 12,000 soldiers occupied the region exceeding 2 million square miles and occupied some 200,000 Native Americans. Except during major campaigns, the troops remained scattered in units of 50-200 men at more than 100 posts, forts, and cantonments across the frontier.”

“The frontier is the outer edge of the wave,” writes historian Frederick Jackson Turner, “the meeting-point between savagery and civilization…the line of most rapid and effective Americanization.” It was the U.S. Army’s role to facilitate this Americanization and expansion into the western frontier. In the quarter century following the Civil War, the Army’s operational experience came to be known as the Indian Wars era.

In the years preceding the Civil War, expressions of the urge to expand into the Western frontier can be found in publications of the day. John Louis O’Sullivan wrote in the July-August 1845 issue of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, “Our manifest destiny is to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” One day in 1851 John Babsone Lane Soule coined the slogan “Go West, young man and grow with the country” in a rather obscure Indiana newspaper called the Terre Haute Express. Horace Greeley, editor of the nationally distributed New York Tribune, popularized the slogan beginning with an 1865 editorial. This phrase became a mantra for manifest destineers and expansionists into the western frontier.

As increasing numbers heeded the call to “Go West,” conflicts with Native Americans escalated. Prior to the Civil War, these conflicts were limited in scope and occurred at a time when the Native American could withdraw or be forced into the frontier. But, by 1865 this “safety valve” was being compromised by multiple travel routes and settlements across the frontier. Inevitably a guerrilla war, characterized by skirmishes, pursuits, massacres, raids, expeditions, battles and campaigns, ensued.

When the eleventh Census was taken June 1, 1890, the population of United States was calculated to be 62,622,250. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Bulletin No. 12 of April 1891 stated that the frontier line of settlement was “so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line…. It cannot, therefore, any longer have a place in the census reports.” In effect the frontier of the United States no longer existed and, therefore, the tracking of westward migration would no longer be tabulated in the census.

This trend prompted Frederick Jackson Turner to develop his milestone Frontier Thesis which he presented at the World Columbian Exposition in 1893. One historian characterizes this thesis, “For Turner, continental expansion, symbolized by the ever moving frontier creating more free land, was the driving, dynamic factor of American progress. It had been since Christopher Columbus, and remained so until the Census Bureau erased the frontier with the keystroke of a typewriter. Without the economic energy created by expanding the frontier, he warned, America’s political and social institutions would stagnate. If one adhered to this way of thinking, America must expand or die.”

This exhibit conveys social and cultural facets of military life in the frontier west through images, quotations, and texts derived from the resources of the Dickinson Research Center. While not a balanced accounting of life due to a focus on the military and a lack of a Native American perspective, the exhibit does explicate the political context for the “Indian Question” issue, the consequent jurisdictional problem faced by the executive and legislative branches of the federal government, and its effect on the lives of both soldiers and Indians on the frontier.

With the closing of the United States frontier, one could pose rhetorical questions about other frontiers and who might be involved in their exploration. Can you think of other geographic frontiers that will be and are being explored? The oceans? Though the oceans cover 70% of the Earth’s surface, scientists estimate that only 5% has been explored so far.

Space, “the final [and ultimate] frontier,” is another obvious answer. One commentator writes “The exploration of Space creates unlimited opportunities for turning billions of people’s dreams into realities. To make space exploration possible, our leaders need the public’s acceptance of the dangers & opportunities: The major elements for space exploration are antimatter energy, space facilities, spacecraft, science & technology, and economic goals.”

What role, if any, will the military have in space exploration? Do you think colonies will be established on the moon? on Mars? Will the military provide the security for their colonization? In what ways are the exploration and permanent human settlement of the space frontier comparable to the exploration, “taming”, and settlement of the West? If encountered, how would extraterrestrials and their worlds be treated?

In today’s world do you see any parallels and/or dissimilarities between the soldiers’ lives in the Army of the West and those deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan? Do you think both their lives were and are dedicated to providing and defending “Homeland Security?”

Images

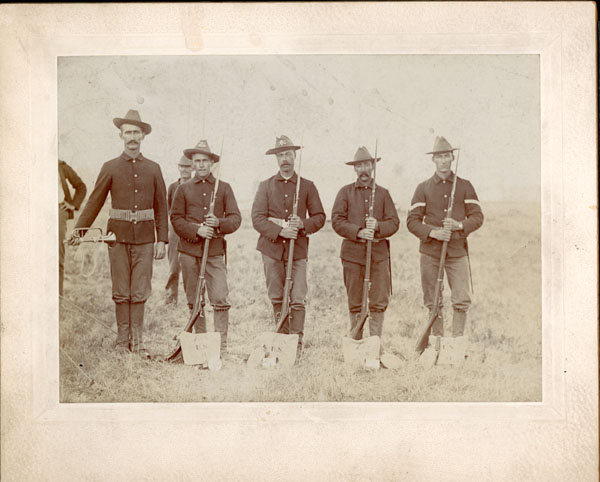

Skirmishers preceded troops traveling in areas where the enemy could be encountered at any time. Only riflemen with marksmanship skill were assigned to skirmish duty and they were ready to go into formation immediately upon seeing the enemy. In December 1890, Private William G. Wilkinson and seven other troopers were sent forward as skirmishers into Sitting Bull’s village to assist the Indian police in arresting him. Wilkinson wrote, “That meant we were to draw fire first, it gave us a peculiar feeling, to go forward like that, in the dark not being able to see what is in front of you, not knowing what minute a bullet with your number on it is coming your way. It is not so bad if you can see where you are going.”

Spanish-American War era Infantryman writes to his loved one prior to moving on to Santiago de Cuba, the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province in eastern Cuba, probably in ground support of the naval battle that would occur on July 3, 1898. He sits with a canvas haversack, canteen and cup at his side and a knapsack and a Krag Jorgenson bolt action rifle nearby.

Love letters, expressions of desire and longing, were typical between married couples. A wonderful example can be found in a September 1, 1861 letter from Alice Kirk Grierson to her husband of seven years General Benjamin Henry Grierson, “Wouldn’t I like to kiss, hug, love and almost devour you if I could only have you to myself today but I suppose you are safe from any such demonstration at present.”

Indicated by the two service stripes on the forearm part of his coat, Mr. Steel had served 10 years in the army at the time of this picture. He prepares to place a stereograph into the stereoscope that Mrs. Steel holds. Similar to the recreational function of today’s DVD player, the stereoscope provided hours of vicarious fun for the viewer who could see three-dimensional images presented on stereographs. By 1859, stereo-mania was infectiously widespread in the United States. With the financial crash of 1873, the demand for stereoviews dropped and production ceased. During the 1880s, the stereoview business witnessed a resurgence with aggressive companies such as Underwood and Underwood.

However, the principal barracks relaxation for those frontier regulars without families stationed at remote posts was visiting and talking among themselves. In 1893 Private B. C. Goodin wrote in his diary that he spent his off-duty time reading in quarters, “strolling, playing cribbage, singing and dancing in quarters, attending an “entertainment” in the post chapel, and playing jokes on his comrades in the barracks.

Wearing a circa 1872 uniform coat, Mr. Chance poses with two children, possibly his daughters. When soldier families in garrisons were present, increased interest in community entertainments was evidenced and expressed through wives and children participation in singing, clog dancing, and variety shows.

However, as historian Don Rickey, Jr. writes, “Isolation, boredom, and monotony characterized the life at the western posts. Because these frontier forts were intended to serve as focal points for offensive and defensive operations against unsettled hostile Indians, they were usually located in regions little touched by white civilization…The Regular Army had no rotation plans during the Indian campaigns, and troops frequently were assigned to the same stations for several years.”

Sanitation and hygiene were considerable issues for any commander of a frontier post. In 1874, General Luther P. Bradley reported that at Fort Laramie the policing of the Laramie River was bad “and the peaks of manure from the cavalry stables and the filth and rubbish from the post, all of which has been deposited for many years on the north side and immediately contiguous to the post, is offensive in every particular.” Moreover, Post Surgeon Hartsnuff complained bitterly of intolerable conditions with respect to these issues in 1877 reporting, The hygienic condition of the post is objectionable. Water closets in the rear of the commanding officers’ quarters, for four or five years reported as a nuisance, still stand, and continue to saturate the atmosphere with noxious odors….Putting of manure, offal, debris, dirt and filth into the pond above and immediately contiguous to the post is productive of the usual results…The stench is at times almost unendurable, especially to the officers who live in nearest proximity to this generative apparatus; besides, a considerable portion of the garrison and all of the stock drink the water of the Laramie that is contaminated from this source…”

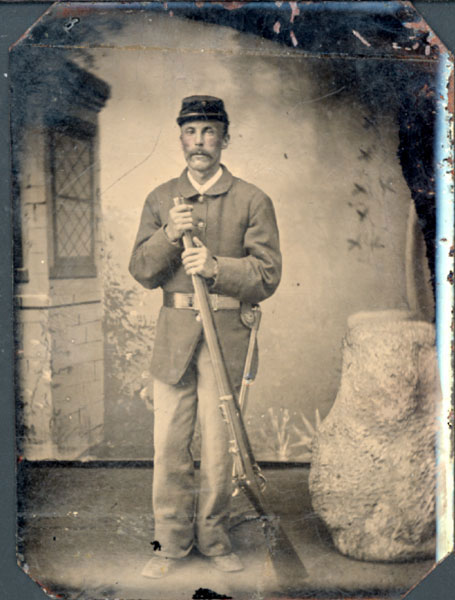

The unidentified, forage-capped soldier, wearing an ill-fitting five-button fatigue coat and bayonet scabbard, holds a Springfield trapdoor rifle.

In a letter from Fort Shaw, Montana Territory dated November 1880, Frances Marie Antoinette Mack Roe, an officer’s wife, opines about the relationships between soldiers, soldiers’ mothers, and the Army “…a soldier’s life is not hard unless the soldier himself makes it so. The service and discipline develop all the good qualities of the man, give him an assurance and manly courage he might never possess otherwise, and best of all, he learns to respect law and order. The Army is not a rough place, and neither are the men starved or abused, as many mothers seem to think. Often the company commanders receive the most pitiful letters from mothers of enlisted men, beseeching them to send their boys back to them, that they are being treated like dogs, dying off starvation, and so on…It is such a pity that these mothers cannot be made to realize that army discipline, regular hours, and plain army food is just what those ‘boys’ need to make men of them.”

Letters provided a means to communicate thoughts, feelings, fears, challenges and difficulties to loved ones. Today these same letters provide an intimate view of people’s lives during times past. In addition, such accounts lend a unique perspective when examined within the broader social and cultural context of the time.

In a letter written in October 1872, Frances Marie Antoinette Mack Roe, an officer’s wife, described an Indian attack on Camp Supply in Indian Territory. “Night before last the post was actually attacked by Indians! It was about one o’clock when the entire garrison was awakened by rifle shots and cries of ‘Indians! Indians!’ There was pandemonium at once. The ‘long roll’ was beaten on the infantry drums, and ‘boots and saddles’ sounded by the cavalry bugles, and these are calls that startle all who hear them, and strike terror to the heart of every army woman…I had firm hold of a revolver, and felt exceedingly grateful all the time that I had been taught so carefully how to use it, not that I had any hope of being able to do more with it than kill myself, if I fell in the hands of a fiendish Indian. I believe that Mrs. Hunt, however, was almost as much afraid of the pistol as she was of the Indians. Ten minutes after the shots were fired there was perfect silence throughout the garrison…Not one word did we dare even whisper to each other, our only means of communication being through our hands. The night was intensely dark and the air was close – almost suffocating.”

Between 1864 and 1870 the “Indian Question” was a major problem confronting the congress and executive department. Two conflicting forces were evident. One demanded the Indian problem be settled by peaceful methods, while the other saw no solution except by the use of force. Moreover, within the executive department this conflict raged between the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior and the War Department. Indian Affairs supervised all Indian superintendents and agents and authorized the distribution of annuities. However, whenever Indian hostilities broke out, the War Department was compelled to intervene until they could be put down. As a consequence, the authority of the two departments overlapped and, therefore, clashed oftentimes with disastrous results.

General Philippe Regis Denis de Keredern de Trobriand records in a journal entry of July 1867 his understanding of the “Indian Question.” Chatting with pioneers in Omaha, Nebraska Territory, De Trobriand writes, “The majority were convinced that the simplest and only means of settling the ‘Indian Question’ was to exterminate ‘all the vermin’…Others, more just and more moderate, believe that the whites have been far from blameless…These latter informants are few in number, and while they declare that the poor Indians have been treated like dogs, that they have been lied to, robbed, pillaged, and massacred, they would be just as prompt as the others in shooting on sight any red-skin suspect that crossed their path. The destiny of the white race in America is to eat up the red men, and in this rising tide of population that rolls towards the setting sun there is not one who is backward in taking his bite.”

These infantrymen, wearing five-button fatigue coats and kepis (or forage caps), hold model 1873 Springfield “trapdoor” rifles. In full field equipment, these soldiers have knapsacks, blankets and bedrolls. A McKeever cartridge box is seen near the standing soldier’s hip.

Initial medical examinations of new recruits were regulated by the U.S. Army. After the recruit strips and bathes the medical officer was to “examine him stripped; to see that he has free use of all limbs; that his chest is ample; that his hearing, vision, and speech are perfect…; that he has no tumors, or ulcerated or extensively cicatrized [scar tissued] legs, no rupture or chronic cuteaneous [sic] affection; that he has not received any contusion, or wound of the head, that may impair his faculties; that he is not a drunkard; is not subject to convulsions; and has no infectious disorders…, nor any other to unfit him for military duty.” Oftentimes, these exams were carelessly done. Upon their arrival from the recruit depot, they were examined again and many were then found medically unfit for duty.

Beginning in 1884 each new recruit was issued a copy of The Soldier’s Handbook, a pocket-sized, leather-bound volume that provided him with the basic knowledge of what the army expected of him and how to take care of himself. Prior to this the recruit had to learn this information by observation and instruction.

In the field picture below are U. S. infantry troops wearing five-button fatigue blouses, campaign hats, and Mills-cartridge belts. They hold Springfield rifles with fixed bayonets and at their feet are haversacks, canteens and cups.

Troops, assembled for campaign service at a regimental headquarters, were sometimes escorted for a few miles by a band, usually playing “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” The infantry in a column swung out with “blanket rolls and haversacks slung over their shoulders, and their tin cups, which hung from the haversack, rattled and jingled as they marched.”

Boudoir card photograph

Five soldier squad with bugler and rifles

W. S. Zinn, Minneapolis, Minnesota, ca. 1890

Photographic Study Collection, 2003.270

According to Old Fort Snelling Instruction Book for Fife, “The Girl I Left Behind Me” was probably an old Irish tune. It became a popular British marching song under the title “Brighton Camp.” In the years before the American revolution, it was often played when a British naval vessel set sail or an army unit left for service abroad. “The Girl I Left Behind Me” was adopted by the Americans and has become a traditional army song especially associated with the Seventh Infantry. It was also a favorite with the troops at Fort Snelling in the 19th century. Even today it is played at the United States Military Academy at West Point as part of the medley for the cadet’s final formation for graduation.”

Although there are several lyrical versions of the song, here is a most common one:

I’m lonesome since I crossed the hill,

And o’er the moor and valley.

Such heavy hearts my thoughts do fill

Since parting with my Sally.

I see no more the fine and gay,

For each does but remind me

How swift the hours did pass away

With the girl I left behind me.

Oh, ne’er shall I forget the night;

The stars were bright above me,

And gently lent their silvery light

When first she vowed she loved me,

But now I’m bound to Brighten’s camp;

Kind heaven may favor find me,

And send me safely back again

To the girl I’ve left behind me.

The bee shall honey taste no more.

The dove become a ranger,

The dashing waves shall cease to roar

Ere she’s to me a stranger.

The vows we registered up above

Shall ever cheer and bind me

In constancy to her I love,

The girl I’ve left behind me.

My mind her form shall still retain

In sleeping or in waking,

Until I see my love again,

For whom my heart is breaking.

If ever I should see the day

When Marshall have resigned me,

Forevermore I’ll gladly stay

With the girl I left behind me.

Dress uniform elements, including dress helmets with dyed horsehair plumes, pictured here are largely from the 1880s and an unusual sight on frontier posts.

In the summer of 1871, Frances Marie Antoinette Mack married Fayette Washington Roe, newly graduated from West Point, and joined his infantry regiment at Fort Lyon, Colorado. By October 1878 Lieutenant Roe was stationed at Fort Shaw, Montana Territory on the banks of the Sun River. Built in 1867 and first named Camp Reynolds, then changed in honor of a Civil War soldier, Colonel Robert Shaw, Fort Shaw was established as a military post in 1876.

In May 1885 after returning to “this dear old post” from the East, Mrs. Roe revels in army life in the West, “I love army life in the West, and I love all the things that it brings to me – the grand mountains, the plains, and the fine hunting. The buffalo are no longer seen; every one has been killed off, and back of Square Butte in a rolling valley, hundreds of skeletons are bleaching there now.”

Three years later and preparing for reassignment, Roe writes, “We know that when we leave Fort Shaw we will go from the old army life of the West – that if we ever come back, it will be to unfamiliar scenes and a new condition of things. We have seen the passing of the buffalo and other game, and the Indian seems to be passing also.”

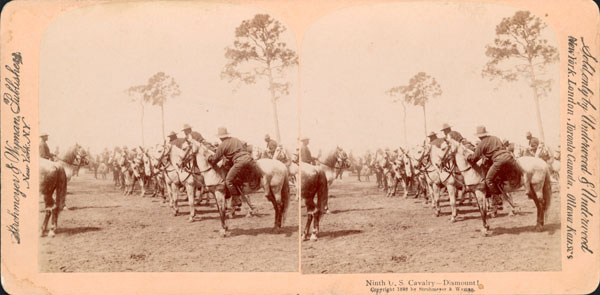

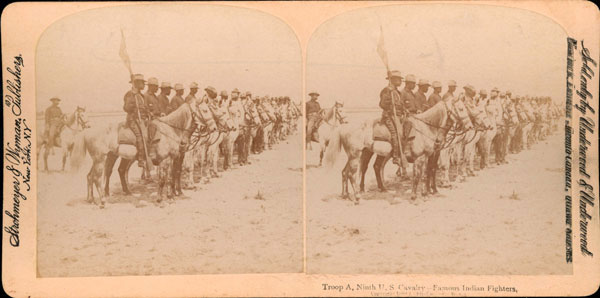

On September 21, 1866, the 9th Cavalry Regiment was activated at Greenville, Louisiana under the command of Colonel Edward Hatch and transferred to the New Mexico District in 1875-76. Two companies were stationed at Fort Bayard, one at Fort McRae, two at Fort Wingate, three at Fort Stanton, one at Fort Union, one at Fort Selden, and one at Fort Garland. In New Mexico, the Buffalo Soldiers participated in campaigns against Victorio, Geronimo, and Nana.

In a letter dated February 25, 1880 Colonel Hatch describes to General Pope the conditions in which the Buffalo Soldiers pursued the Apache,”…the work performed by these troops is most arduous, horses worn to mere shadows, men nearly without boots, shoes and clothing. That the loss in horses may be understood when following the Indians in the Black Range the horses were without anything to eat five days except what they nibbled from piñon pines, going without food so long was nearly as disastrous as the fearful march into Mexico of 79 hours without water, all this by forced marches over inexpressably [sic] rough trails…It is impossible to describe the exceeding roughness of such mountains as the Black Range and the San Mateo. The well known Modoc Lava beds are a lawn compared with them.”

In 1898 elements of the 9th cavalry regiment fought in Cuba during the Spanish- American War and took part in the charge up San Juan Hill.

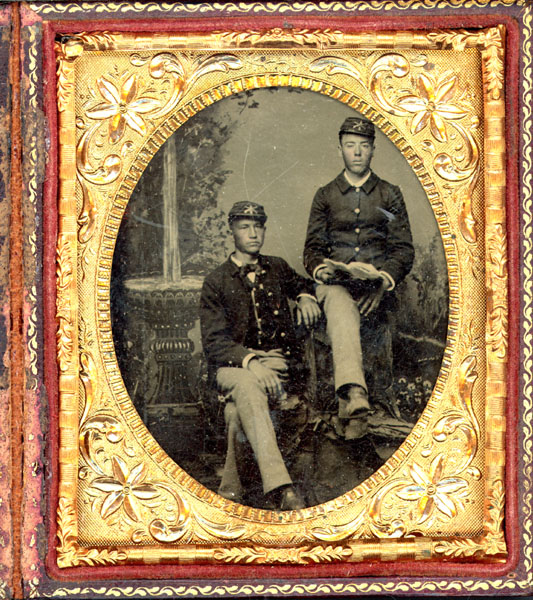

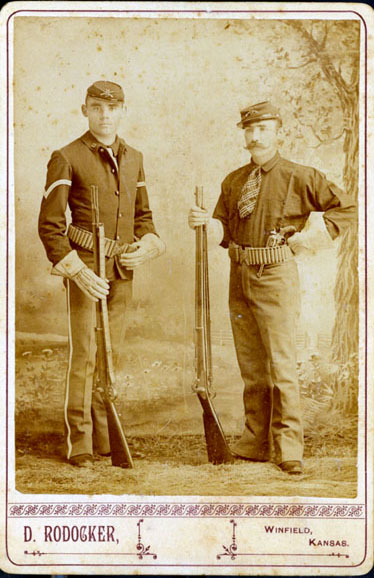

Two forage-capped, U.S. infantrymen, both wearing Mills-pattern woven cartridge belts with U.S. closure plated, hold Springfield trapdoor rifles. The soldier on the right wears a non-regulation tie and carries a non-regulation Colt lightning revolver.

“The food supplied to soldiers,” writes historian Don Rickey, Jr., “largely determines their efficiency, health, and psychological well-being…From 1865 through the early 1890’s, the mainstays of soldier menus were hash, stew (slumgullion), baked beans, hardtack, salt bacon, coffee, coarse bread, contract-supplied range beef, and some condiments, such as brown sugar, salt, vinegar, and molasses.” These “mainstays” were supplemented when and where possible by commissary department foods such as flour, beans, and salt pork. They were also supplemented by game hunting and post and company gardens that supplied fresh produce.

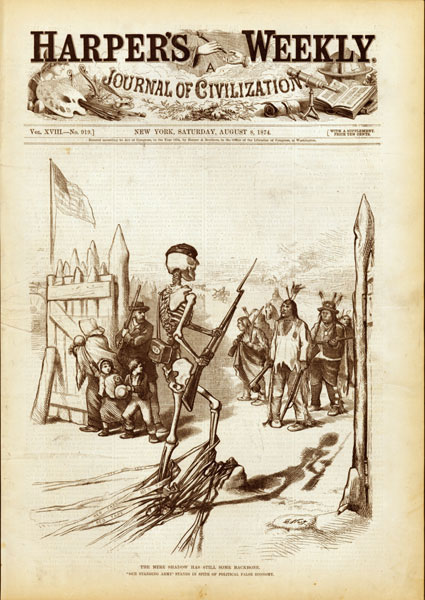

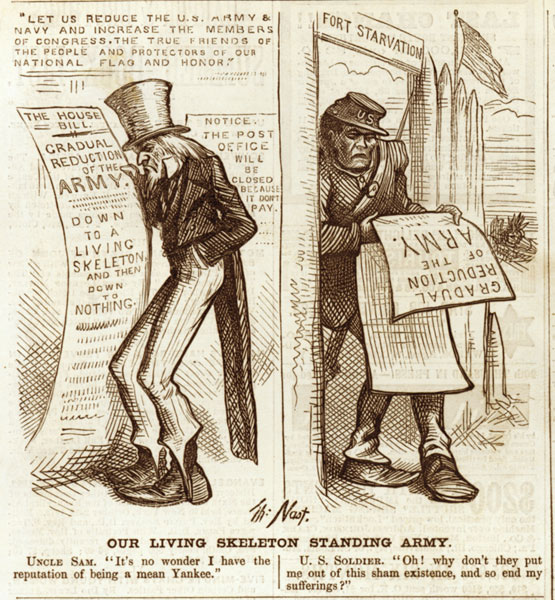

Drawing for Harper’s Weekly between 1859 and 1860 and 1862 until 1886, Thomas Nast (1840-1902) was a caricaturist and political cartoonist of national renown. In 1873, following his successful campaign against New York City’s Tweed Ring, Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall, he was billed as “The Prince of Caricaturists” for a lecture tour that lasted seven months. He popularized the elephant to symbolize the Republican Party and the donkey as the symbol for the Democratic Party, and created the “modern” image of Santa Claus. Following his death he was attributed the moniker, “Father of American Caricature.”

Through these cartoons, Nast, a Republican and supporter of the military, ridiculed and condemned the Democratic Congress for even the suggestion of reducing the U.S. Army during an era of Indian warfare on the frontier. More specifically, these cartoons lampoon the House of Representatives bill, H. R. 2546, which provided for the gradual reduction of the Army of the United States. On May 23, 1874, Republican Indiana Representative John Coburn from the Committee on Military Affairs reported the bill. On June 1 the House passed the bill and requested the concurrence of the Senate. The bill was referred back to the Committee on Military Affairs.

Engraving The Horse and His Rider Thomas Nast, Harper’s Weekly, June 27, 1874 Arthur & Shifra Silberman Native American Art Collection, 1996.027.1461.203

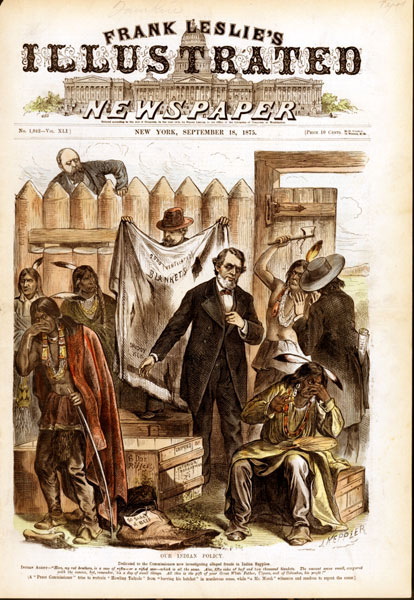

Caricaturist Joseph Ferdinand Keppler (1838-1894) was hired by Frank Leslie about 1873 and by 1875 he was in charge of drawing most of the cover cartoons for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. He left in 1876 to found the newspaper, Puck. Specializing in cartoons that attacked President Ulysses S. Grant and political graft, Keppler here ridicules the U.S. Indian policy through the caricature of alleged frauds in Indian supplies from peace commissioners. He shows a man offering Indians torn (“ventilated”) blankets, an empty rifle case, and (“50 sides of”) spoiled beef.

As an English traveler through the Rockies in 1873, Isabella Lucy Bird (1831-1904) in her 1879 book, A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, wrote with prejudice about this policy, “The Americans will never solve the Indian problem till the Indian is extinct. They have treated them after a fashion which has intensified their treachery and ‘devilry’ as enemies, and as friends reduces them to a degraded pauperism, devoid of the very first elements of civilisation. The only difference between the savage and the civilised Indian is that the latter carries firearms and gets drunk on whisky. The Indian Agency has been a sinkof fraud and corruption; it is said that barely thirty per cent of the allowance ever reaches those for whom it is voted; and the complaints of shoddy blankets, damaged flour, and worthless firearms are universal. ‘To get rid of the Injuns’ is the phrase used everywhere. Even their ‘reservations’ do not escape seizure practically; for if gold ‘breaks out’ on them they are ‘rushed,’ and their possessors are either compelled to accept land farther west or are shot off and driven off.”

Except for the gauntlets, Gibhart is wearing all non-regulation clothing and arms. Dressed in a frontiersman outfit of tailored and fringed buckskin, this military scout sports a Colt single action Army revolver in a civilian holster with a money/cartridge belt. He holds a Marlin rifle. Troop F of the 8th Cavalry served at Fort Meade, South Dakota, before being transferred to Fort Sill, Oklahoma on April 24, 1898.

Born in 1845, Theodore Baughman in his circa 1886 autobiographical book entitled The Oklahoma Scout, offers an insight into the mind of a government scout. “My business in hunting and driving cattle, locating ranches, etc., threw me constantly in contact with the United States troops stationed at the various posts. My accurate and extensive knowledge of the country, as well as a natural aptitude for finding my way anywhere, soon became known to the officers commanding, so that my services were in demand to pilot detachments of troops in their expeditions. I may remark here that from early boyhood the bump of locality, as the phrenologists would say, was strongly developed on my cranium. I never experienced the feeling of being lost. I have read somewhere that a poet is born, not made, and I think the same is true of a successful scout. Going through a country for the first time I make mental note of all its leading features, and they remain so indelibly impressed upon my memory that on a second visit it seems familiar ground. This is not the case with the majority. I know plenty of men who have been through a country time and again who would confess themselves incompetent to act as a guide to anyone else through the same region. And, after all, in every enterprise of life, is it not true that only the few can find their way unaided, while the many must be content to follow as they are guided?”