The word, “cowboy,” means many things to many people. While it denotes a certain lifestyle or way to make a living, it can also connote both laudable and reprehensible behaviors. For more than a century, wordsmiths in a variety of fields have employed and evoked imagery based upon the reality, iconography, and mythology of the American cowboy. Historians, journalists, pundits, and poets have employed figures of speech rooted in this imagery to conjure up in the reader’s mind both exalted and pejorative images of the cowboy and the persons to whom he is compared.

Nineteenth-century journalists described and portrayed the cowboy in both realistic and romantic ways to their readers. In an 1882 Texas Live Stock Journal issue, one writer, employing metaphors and similes, offered romanticized notions about the cowboy as follows: “We deem it hardly necessary to say in the next place that the cowboy is a fearless animal,” and “As another necessary consequence to possessing true manly courage, the cowboy is as chivalrous as the famed knights of old.” Coincidentally, a Cheyenne Daily Ledger writer suggested a less glamorous regard for the cowboy: “Morally, as a class, they are foulmouthed, blasphemous, drunken, lecherous, utterly corrupt.” From these statements one can discern the seeds from which the complex imagery and mythology of the cowboy grew.

This cowboy imagery had implications for the nation’s politics. Since Teddy Roosevelt’s ascendancy to the presidency, politicians, depending upon political persuasion, have been either accused of or acclaimed as acting like or being cowboys. Upon hearing the news of President William McKinley’s assassination in 1901, Senator Mark Hanna of Ohio reportedly lamented, “Now look! That damned cowboy is president.” Roosevelt fostered this image by frequently presenting himself as a cowboy. He was the first to symbolize the cowboy on a national level. In recent times, pundits have identified Lyndon Johnson as a Texas cowman, Ronald Reagan was sometimes seen as a trigger-happy cowboy shooting from the hip, and George W. Bush has been known by the sobriquet “cowboy president.” The comparison of politicians to the real or imagined character and lifestyle of the cowboy continues.

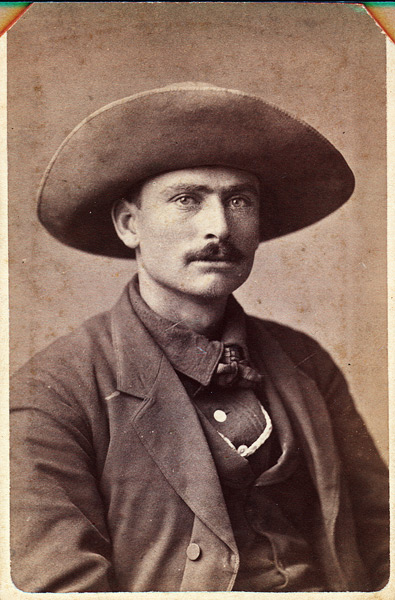

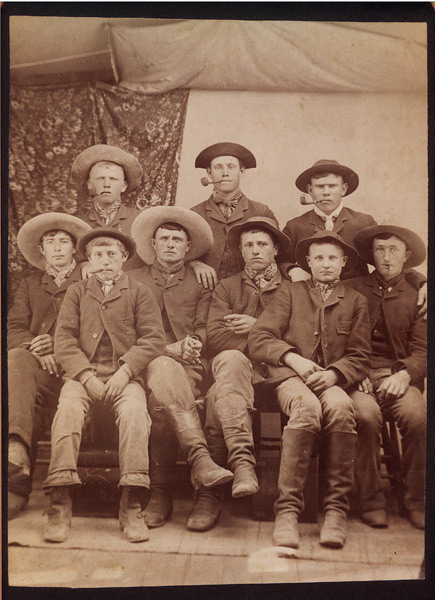

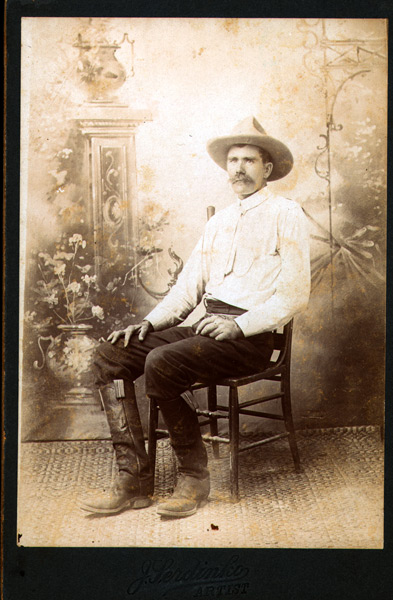

Dating primarily between 1880 and 1910, the vintage photographs on display here are of authentic cowboys (hired men who tend cattle and perform many of their duties on horseback). Juxtaposed against these real cowboy images are quotations from popular culture and the media that employ figures of speech evocative of both disparaging and lofty cowboy imagery. This contrast will challenge preconceived notions of who or what is a cowboy, instill an awareness of and appreciation for the evolution of this cowboy imagery, and broaden understanding of the American cowboy.

This virtual exhibit combines vintage photographs of real American cowboys with the writings of historians, journalists, political pundits, and poets. The historians and journalists write about the real life of the cowboy. The pundits and poets employ “cowboy” as a metaphor or figure of speech. Some quoted pundits use the word “cowboy” critically in describing certain politicians, while others are laudatory. Use of such quotations does not imply agreement with these views by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. The exhibit is intended to educate and challenge the viewer about the reality and imagery of the American cowboy.

In “Cowboy dreams” posted on the Guardian Unlimited website, June 11, 2004, Philip James writes, “When Ronald Reagan declared the Soviet Union an “evil empire”, it was a dramatic, grand gesture. Finally a US president introduced moral clarity to the cold war, after decades of accommodation and stalemate. But he did not follow by preparing to invade East Germany. Reagan may have sounded like a cowboy, but he acted like a diplomat. Dispatching George Shultz to Moscow countless times was the embodiment of the doctrine ‘walk softly and carry a big stick’…The pretender to Reagan’s legacy sounded like a cowboy when he lashed out at the ‘axis of evil’ in his 2002 state of the union address and then proceeded to act like one. He had been preparing for war for two years before he made the speech.”

Allison Fuss Mellis in her 2003 book, Riding Buffaloes and Broncs: Rodeo and Native Traditions in the Northern Great Plains, writes, “After 1889, the various bands of Lakotas that settled on the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation forged a new collective identity as Cheyenne River Sioux. For many this new identity came to include a sense of themselves as cowboys…By this time [1900], many Lakotas had already begun to forge a new Indian identity as both Cheyenne River Sioux and cattle ranchers, because they chose to keep working as cowboys on both remaining tribal and recently sold non-Indian ranches.”

From Ann Nolan Clark’s The Singing Sioux Cowboy Reader, 1954:

“lak’ota pte’ole hoksila hemaca….sunk’ akanyanka mak’oc’e o’unyanpi ekta omawani.”

Translated: “I am a Sioux cowboy….I ride the range.”

Rufus S. Zogbaum in his article, “A Day’s ‘Drive’ with Montana Cowboys,” appearing in the July 1885 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, wrote, “A picturesque, hardy lot of fellows, these wild ‘cowboys’ as they sit on the ground by the fire, each man with his can of coffee, his fragrant slice of fried bacon on the point of his knife-blade, or sandwiched in between two great hunks of bread, rapidly disappearing before the onslaughts of appetites made keen by the pure, invigorating breezes on these high plains. See that brawny fellow with the crisp, tight-curling yellow hair growing low down on the nape of his massive neck rising straight and supple from the low collar of his loose flannel shirt, his sun-browned face with the piercing gray eyes looking out from under the broad brim of his hat…”

At the Back Fence “So Many Cowboy…So Little Rope” posted on www.likesbooks.com, Issue #93 (April 15, 2000): “Whoa, there. Maybe it’s time to wake up and smell the manure. What are ‘real’ cowboys like? ‘More Gabby Hayes than John Wayne,’ says Harlequin author Julie Kistler (who’d rather write about men in tuxedoes than men in chaps), bringing to mind a scruffy, bewhiskered, bowlegged, tobacco-chewing cow puncher with bad skin, bad teeth and creaky arthritic joints. Not a character we’ll see on the cover of a romance novel any time soon!”

Many historians agree that the myth, legend and heroic concepts of the cowboy have their origins in the years of the open range cattle industry during the last part of the 19th century, more specifically the years from 1865 to 1895. It is estimated that six to nine million head of cattle were driven by cowboys from Texas to Kansas between 1867 and 1886. Most of these cowboys were in their twenties. Lonn Taylor wrote in his 1983 book, The American Cowboy, “Cowboying was not an old man’s job, or even a middle-aged man’s job, and ten years of hard riding was about all the human body could take…. Cowboying was almost exclusively the work of one generation: the children who were born just before the Civil War, grew to maturity in the Reconstruction South, and entered manhood in the 1870s and 1880s.”

In an excerpt from her 2003 Rough Rider in the White House: Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of Desire, Sarah Watts writes, “In 1885, returning East after a bighorn hunting trip to Montana, Roosevelt had another studio photo made. This time he appeared as a self-consciously overdressed yet recognizable Western cowboy posed as bold and determined, armed and ready for action. ‘You would be amused to see me,’ he wrote to Henry Cabot Lodge in 1884, in my ‘broad sombrero hat, fringed and beaded buckskin shirt, horse hide chaparajos or riding trousers, and cowhide boots, with braided bridle and silver spurs.’ To his sister Bamie, he boasted, ‘I now look like a regular cowboy dandy, with all my equipments finished in the most expensive style.'”

In describing cowboy characteristics, Alfred M. Williams in an article entitled “An Indian Cattle-Town” appearing in the February 1884 issue of Lippincott’s Magazine wrote, “It is needless to say that they are all hardy, bronzed by the sun to a deep red unless nature has given a darker pigment to their skin, keen-eyed, and of the free and reckless carriage natural to their manner of life, long-haired flaphatted, and dressed in the rough-and-ready garments of the frontier. Not infrequently there is a border-dandy among them, who is as punctilious in regard to his dress and accoutrements as a fashionable exquisite, and quite conscious of the elements of picturesqueness in his appearance. Such a one will show a set of white teeth through his moustache, and will very probably carry a toothbrush in his bootleg, while his locks are carefully oiled and his slouched hat is set on at an accurate angle.”

In the May 17, 1901 Arapaho Bee, “LYNCHED. A Free Grass Mob Hangs Herd Law Man. Mr. J. L. Chandler, a resident of Ioland, Day county, was taken from his home by a posse of cattlemen and hanged. The lynching party was composed of Day county cattlemen. There has been trouble between the farmers and cattlemen of for some time. During the past few weeks the trouble has been growing graver and many cattle have died of poisoned water. Mr. Chandler was suspected of being one of the party who has been poisoning the water and he was lynched as a warning to others…This is the first lynching that has occurred in Oklahoma since its organization as a territory…The lynching of this man at Ioland will probably mould sentiment very rapidly against free grass and we can look for those in authority to say a man’s farm is his own and if you want his grass or anything else on that farm go and get it from the owner.”

Andrew Bernstein in his article “In Defense of the Cowboy” in the February 26, 2003 Ayn Rand Institute’sMediaLink writes that those opposing the war with Iraq believe America “is acting like a ‘cowboy.'” He writes that a New York Times article explained that “to some Europeans the ‘major problem is Bush the cowboy.’..U.S. Senator Chris Dodd of Connecticut agrees, stating that America must not ‘act like a unilateral cowboy’…But to most Americans, the cowboy is not a villain but a hero. What we honor about the cowboy of the Old West is his willingness to stand up to evil and to do it alone, if necessary. The cowboy is a symbol of the crucial virtues of courage and independence.”

In the Texas Live Stock Journal of October 14, 1882 an article entitled, “The Cowboy” describes the cowboy: “In the use of the lasso and profane language the cowboy has no equal. He can rope a steer, throwing the noose on either foot of the animal as it runs at full speed, at the same time showing a choice in the matter of selecting appropriate anathemas, which he can deliver equally well, either in Mexican or United States language.”

The October 7, 1872 Denver Daily Times reported, “A herder near Pueblo, named Albert Jones, a few nights ago, became sleepy and tied himself on his horse with his lariat. He was found dead, having been dragged and jumped over the prairie for a long distance.”

From the Trinidad Weekly News, March 12, 1886 in an article titled, “Facts for Would-Be-Cowboys,” the author explains to those thinking of “trying a season’s riding” that “Your ‘outfit,’ or bed, clothing and equipments, will cost you half your earnings and if you smoke freely and do not try to save money, the end of the season will leave you neither richer or poorer. You will often have a wet bed and thank Heaven for getting to it wet as it is; you will eat coarse food, everything fried in lard; you will be in saddle from 12 to 18 hours a day; you will often suffer for the want of food and water during a long day’s work in the hot sun; you will expose yourself to some peril of life and more of limb;…you will vow three times a day that when you strike the ranch again you will quit; you will be sore and bruised, cold at night scorched by day; wet to the skin one hour and parched with thirst the next; and for the rest of your life you will look back to your life on the range with longing thoughts of its charms.”

The Cattlemen’s Advertiser of Trinidad, Colorado, reported on December 2, 1886, “A cowboy named Baker, herding near Bozeman, Montana,…conceived the idea of running a race with a freight train just passing. Putting spurs to his bronco he caught up with the flying cars, and for awhile the race was an even one. While galloping along side the train, by a sudden lurch the horse and rider were thrown against the cars with fatal results. The poor horse was instantly killed. The cowboy also.”

From Harry E. Chrisman’s 1982 book, The 1,001 Most-Asked Questions About the American West: “The originals [cowboys] were basically herdsmen, with a loyalty first to the animal they tended, second to the boss who paid them, and last to themselves and their best fortune…They smelled of cow and horse dung, and seldom bathed. They wore beards that easily became nests for lice, fleas, or other vermin and provided secure foci of infection for barber’s itch. Their underclothes were changed periodically, spring and winter, and were washed when occasion permitted. They also wore the burns and scars from the sun’s rays and the blisters from the cold as we today wear our pallid complexions from indoor work throughout the changing seasons.”

From parentcompany.com as part of “A Science Kit about Design”:

Section 1: Design in Nature: Predation and Defense: “The cowboy fungus. An earthy example of intelligent and purposeful design in living creatures is that of the predatory molds. There are many species of soil mold which capture and feed upon the tiny, exceedingly numerous nematode worms which inhabit the soil. Some of these molds grow sticky knobs with which they entrap the worms. But the star predatory mold species is Arthrobotrys dactryloides, which lassos its prey like a cowboy lassos steers. It is only when nematodes are present in the soil that this mold grows tiny loops, each one formed of three cells. When a worm chances to stick its neck into one of the loops, within one-tenth of a second the loop cells swell and the loop clamps shut on the worm, strangling it. The worm is then digested at leisure. The cowboy fungus has struck again!”

Folklorist John A. Lomax, in collecting songs sung by cowboys, wrote in his 1910 edition of Cowboy Songs, “That the cowboy was brave has come to be axiomatic. If his life of isolation made him taciturn, it at the same time created a spirit of hospitality, primitive and hearty as that found in the mead-halls of Beowulf…He played his part in winning the great slice of territory the United States took away from Mexico. He has always been on the skirmish line of civilization. Restless, fearless, chivalric, elemental, he lived hard, shot quick and true, and died with his face to the foe…He sits his horse easily as he rides through a wide valley, enclosed by mountains, clad in the hazy purple of a coming night…Dauntless, reckless, without the unearthly purity of Sir Galahad though as gentle to a pure woman as King Arthur, he is truly a knight of the twentieth century.”

Christopher Hitchens in his article “Fighting Words ‘Cowboy’: Bush challenged by bovines” for slate.msn.com posted on January 27, 2003 discusses the term ‘cowboy’ and its usage. “Still a third implication is that of the lone horseman, up against the world without more than his six-shooter and steed and lariat. He might be a stick-up artist and the terror of the stagecoach industry, or he might be a solitary fighter for justice and vindicator of the rights of defenseless females. Henry Kissinger never quite recovered from the heartless mirth he attracted when he told Orianna Fallaci that Americans identified with men like himself – the solitary, gaunt hero astride a white horse (as opposed to the corpulent opportunist academic leaking to the press aboard a taxpayer-funded shuttle).”

In an interview in The New Republic, December 16, 1972 Henry Kissinger, Secretary of State under President Richard Nixon, once attributed the success of his “shuttle diplomacy” to the fact that he always acted alone like “the cowboy leading the caravan alone astride his horse, the cowboy entering a village or city alone on his horse. Without even a pistol, maybe, because he doesn’t go in for shooting. He acts, that’s all.”

William T. Larned wrote in an article entitled “The Passing of the Cow-Puncher” in Lippincott’s Magazine, August 1895, “The cowboy, like the buffalo, is fast becoming extinct. In the dawn of the new century now approaching he will be regarded as a curiosity. Ten years hence he will almost have attained the dignity of tradition. History which embalms the man in armor and exalts the pioneer, holds a place for him…Before civilization devours his identity let us try to detain it a moment in its real likeness and garb…Ever since Achilles ‘punched’ cows for King Admetus, the cowboy in all climes has claimed kinship with things classical.”

Having read an article about a play in France called “George W. Bush ou Le Triste Cowboy de Dieu” (George W. Bush or God’s Sad Cowboy), Eric (surname unknown) responds on May 29, 2003 in a Midland, Texas blog called The Fire Ant Gazette declaring that he did not understand why the French thought calling somebody a cowboy was an insult. He wrote, “I reckon that if the worst thang folks could call me was cowboy, I’d be pretty dang happy with that monicker [sic]. ‘Cause here’s what being a real cowboy means…He don’t sit around talkin’ about something that needs doin’ until it cain’t be done…he gits on his horse and he goes and does it…There’s no friend like a cowboy; he’ll tell you when you’re wrong, help you make it right, and go to hell and back with you or for you, whichever the situation calls for.”

Excerpts from Song of the Cattle Trail by Anonymous

The dust hangs thick upon the trail

And the horns and the hoofs are clashing,

While off at the side though the chaparral

The men and the strays go crashing;

But in right good cheer the cowboy sings,

For the work of the fall is ending,

And then it’s ride for the old home ranch

Where a maid love’s light is tending.

Then it’s crack! crack! crack!

On the beef steer’s back,

And it’s run, you slow-foot devil;

For I’m soon to turn back where through the black

Love’s lamp gleams along the level.

He’s trailed them far o’er the trackless range,

Has this knight of the saddle leather;

He has risked his life in the mad stampede,

And has breasted all kinds of weather.

Kathleen Parker in her June 3, 2002 article entitled “Oh, yeah? Well yippie-yi-o-ki-yay to you, too” on townhall.com asks the question “what’s so all-blame wrong with being a cowboy” in light of Iran’s Defense Minister Ali Shamkhani statement, “Bush thinks he is still living in the age of cowboys, and that the world is like Texas with him as its sheriff.” She writes, “But the real cowboy, the genuine driver of cattle across lonely, death-around-every-corner prairies and torrential rivers was the American heroic prototype – strong, brave, trustworthy, loyal, wise, resourceful, self-reliant and dutiful. Sort of like a Boy Scout, except not as clean.”

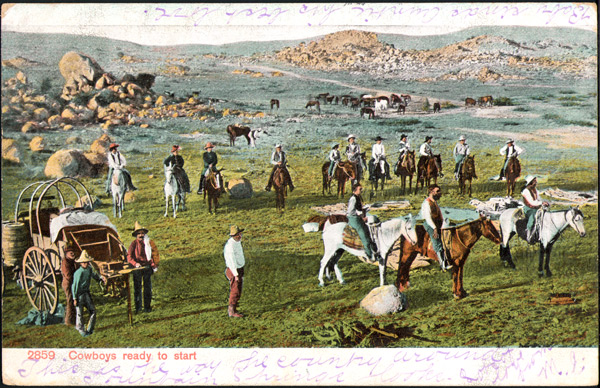

Postcard

Postcard

Branding cattle out west

Adolph Selige, St. Louis, Missouri, 1907

2003.022.2

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

An article entitled “Cowboys’ Hard Work,” published in the August 28, 1890 issue of the Georgetown Courier describes branding time: “There is one opening [in the branding pen] through which the cattle are driven, and the center of the corral is marked by a large snubbing post two feet in diameter. A roundup outfit on coming to the pen may meet some other outfit similarly bent, in which event they join herds and forces. As many of the cows and calves as will fill the corral are forced through the entrance and locked in, and then the fires are lighted and the fun begins. Every calf is branded with the brand on its mother, the roper calling the brand to the men at the fires, as he rides up dragging the victim. As fast as a pen full is branded it is turned loose on the range and the pen is refilled from the herd.”

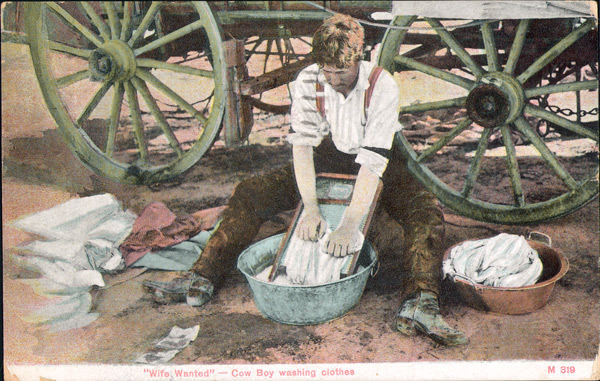

Postcard

Postcard

“Wife Wanted” – Cow Boy washing clothes

Chas. E. Morris, Chinook, Montana, 1909

2003.037

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

According to “Cowpunchers! – Sensible Advice to Sensible Cowboys,” in the June 1885 issue of theTrinidad Weekly News, a cowboy should “get up in the morning when you are first called, or you will be apt to rise rapidly on the toe of the foreman’s boot…Take a good wash. It is most refreshing and prevents sore eyes and other things. If there is no pool or stream of water don’t use up all the water in the water butt [barrel], remember good drinking water can’t be found everywhere, and it is considerable trouble for the cook to fill that butt. Don’t open your eyes under water. If it is very dry and dusty and in alkali country don’t wash your face at all…If you have drawn water from the water barrel just leave the faucet open and the water dropping out and wasting, if you want to get a blessing from the cook. Leave dirty water in the wash pan if you want your brother cowpuncher to love you.”

Philip Ashton Rollins in his book, The Cowboy, describes how a cowboy prepares for a visit to a typical cowtown. “Clean shirts and neckerchiefs were donned – clean as measured by masculine standards, but not unduly clean nor very free from wrinkles. The cleansing, having been performed at the ranch, had been limited to soaping the articles and then anchoring them for a day or so in a running stream. This passive form of laundering usually was gauged by lapse of time, rather than by visible results.”

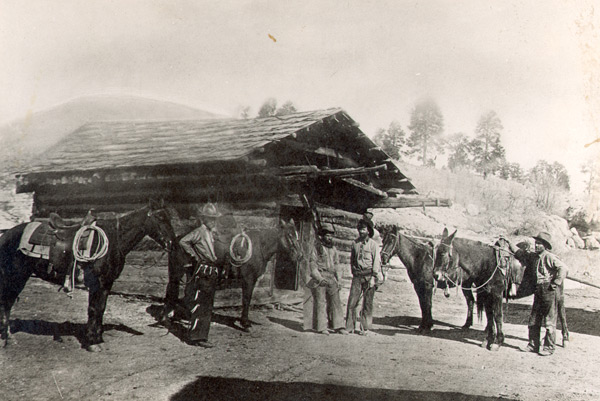

Cabinet photograph

Cabinet photograph

Two cowboys, perhaps one named Johnnie Reedy, with horses

Unknown photographer, ca. 1910

2003.039.3

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

From James Edward Hungerford’s poem, “Land o’ Freedom”:

I want to be boss

O’ a little bronc hoss,

That has got heaps o’ git-up-an’-git,

With an unbroken pride,

An’ a free-swingin’ stride,

That will never lay down ‘er say quit!

I want to be dressed

In the duds I like best,

An’ havin’ the freedom I crave,

Out there in the West,

In the land o’ sweet rest,

In the home o’ the free an’ the brave!

An article in the December 2, 1897 Edmond Republic reads: “What has become of the old fashioned cowboy, who used to ride into our city on his bucking bronco from the range with lariat and Winchester swinging from his saddle and when he walked the streets in his high-heeled boots, the ‘clinkety-clank’ of his spurs could be heard a block away? He was the king of the town. He took the best on sight and when he left the town, he rode down Main street, shooting out windows and terrorizing the people. He made news items plenty and then business good. Civilization has made him a memory only, but business is still good, though news items are scarce. Some days it would prove a relief if the old fashioned cowboy would return.”

Cabinet photograph

Cabinet photograph

Cowboys and cattle

Unknown photographer, ca. 1910

2003.039.4

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

In his 1927 book, Jinglebob, Philip Ashton Rollins writes, “America has had two types of cowboy, the synthetic and the real. The better known cowboy, the synthetic, is the son of imagination; and, living upon a cattle range which is bounded by either the covers of a novel or the edges of a silvered screen, he has indefatigably devoted himself to the rescue of ranch-owning heiresses and to the extinction of their scheming and amative foreman…But America has had also the real cowboy. He dwelt upon the cattle range of actuality; and, there being in this latter and almost womanless realm no heiresses available for succor and but very few dishonest foremen, the real cowboy was compelled prosaically to earn money wages by herding live stock.”

Rick Montgomery in his February 16, 2003 article in the Kansas City Star entitled, “Beaucoup tribulations: French, Americans give each other the eye,” posted on Kansascity.com writes, “The French word for cowboy, for example, is “cowboy.” A near-epithet so linked to the swaggering American stereotype — and now to the U.S. president from Texas — the French do not even have an apt word of their own. So in editorials attacking President Bush’s willingness to use military force, it’s: Bush, ce cowboy de l’Ouest, (Bush, this cowboy of the West) or l’attitude cowboy de Bush (the cowboy attitude of Bush). He talks like a cowboy from the Hollywood movies, they argue, and he carries himself with the squinty-eyed confidence of someone hiding a six-shooter under the flap of his coat.”

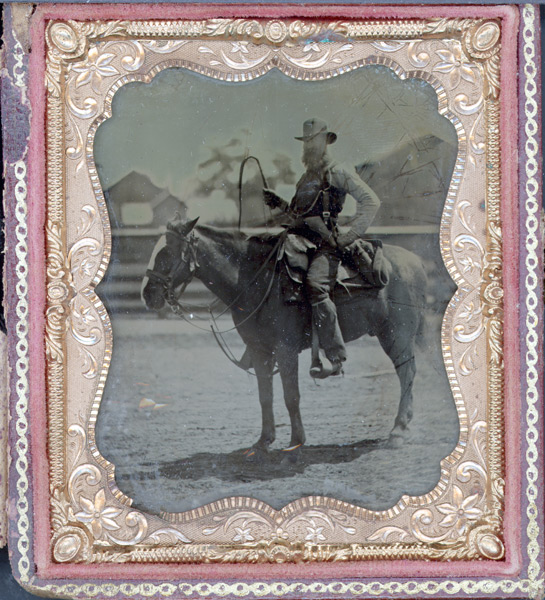

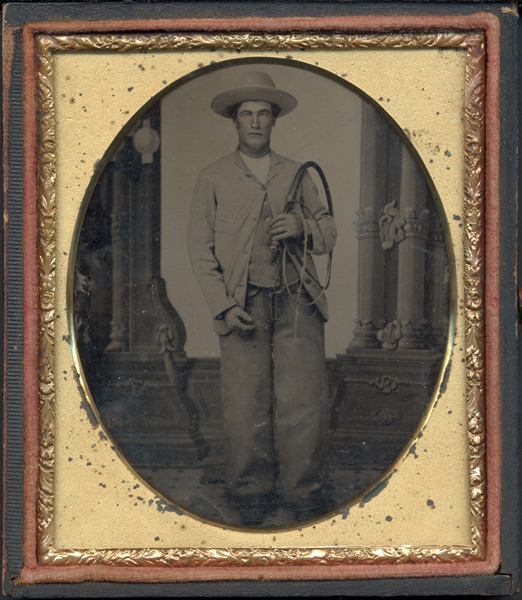

Tintype

Tintype

Two standing cowboys in studio

Unknown photographer, ca. 1890

2003.042.2

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

Bill Straub in his article, “Latest ‘cowboy president’ shoots from hip,” November 28, 2002 on the Seattle Post-Intelligencerwebsite writes that President Bush has earned the sobriquet ‘cowboy president.’ “From his affinity for boots, Stetsons and large belt buckles to his willingness, even desire, to go it alone on vital international issues, Bush projects the image of the cowboy – a man who views the world in terms of good and evil and believes in action…Bush is not the first or only president to be referred to as a cowboy, although several of his predecessors have been described similarly for various reasons. Teddy Roosevelt, the old Rough Rider, really was a cowboy, operating a pair of ranches in the Dakota badlands. Lyndon Johnson, a schoolteacher by trade and politician by temperament, operated his own Texas ranch along the Pedernales River…The ‘cowboy president’ who most resembles Bush is one of his political heroes – Ronald Reagan. Reagan grew up in the non-cowboy town of Dixon, Ill.”

Jeff Bransford, a character in Eugene Manlove Rhodes’ story, “Good Men and True,” explains what a cowboy is: “In the first place, take the typical cowboy. There positively ain’t no sich person! Maybe so half of ’em’s from Texas and the other half from anywhere and everywhere else. But they’re all alike in just one thing – and that is that every last one of them is entirely different from all the others. Each one talks as he pleases, acts as he pleases and – when not at work – dresses as he pleases.”

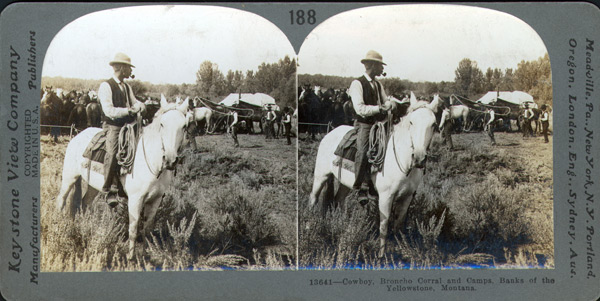

Stereograph

Stereograph

Cowboy of the prairies – Morley, Alberta, Canada

Underwood & Underwood, New York, New York, 1900

2003.051

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

In the July 2, 1885 Trinidad Daily Advertiser the following tale was told: “A cowboy just returned from the roundup was heard in a Butte resort…explaining how intelligent was the dog which lay at his feet: ‘Last week,’ said he, ‘while we was cutting out my boss’ spring beeves from the roundup herd, I seed that ‘ere dog around among the animals examining ’em very close. I wondered what the dickens he was at, an’ kep’ my eye on him. Purty soon he waltzed up close to a steer an’ after lookin’ at it a minute, he run around it an’ drove it out of the herd into our bunch. Then he went back an’ purty soon he chased another’n out. After he’d did it several times, I dropped to it. He was jest a-watchin’ for the boss’ brand and whenever he’d see a critter with it on he’ drive him right slap out into our bunch. Here! Zip!’ and he scooped a handful of crackers from the bowl on the bar and tossed them one by one to the clever dog, who caught them neatly on the fly, while the admiring crowd stood by watching.”

Cased ambrotype

Cased ambrotype

Bearded cowboy with stock whip on horseback

Unknown photographer, ca. 1865

2003.079

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

Regarding cowboys “packing iron,” Philip Ashton Rollins in The Cowboy writes that considering the 2.25 pound weight of a Colt revolver and the additional weight of the ammunition, cowboys did not routinely carry firearms. “When one recalls also that the average cowpuncher was not an incipient murderer, but was only an average man and correspondingly lazy, then one realizes to be true the statements that the average puncher was unwilling to encumber himself with more than one gun, and often even failed to “go heeled” (armed) to the extent of “packing” (carrying) that unless conditions insistently demanded.”

From “The Cowboy,” an anonymous poem, ca. 1884:

“What is it has no fixed abode.

Who seeks adventures by the load–

An errant knight without a code?

The cowboy.

Who is it when the drive is done,

Will on a howling bender run,

And bring to town his little gun?

The cowboy.”

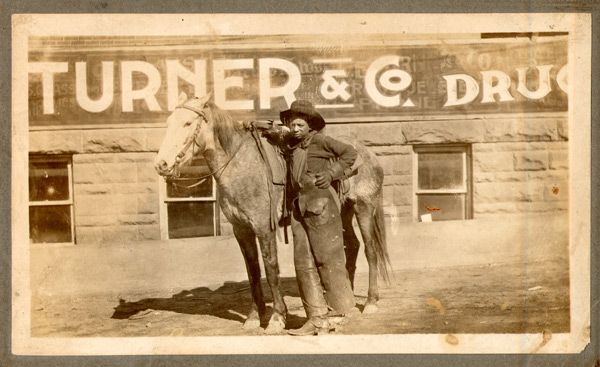

Cabinet photograph

Cabinet photograph

Young African American cowboy standing by his horse

Unknown photographer, ca. 1890

2003.105

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

Undertaken between 1937 and 1939, the Slave Narrative Project of the Federal Writers’ Project recorded the remembrances of elderly African Americans who had been born into slavery. Coming to Texas from Alabama as a slave in 1862, Tom Mills worked cattle in South Texas. Mills recalled, “When I got to workin’ for myself, it was cow work. I done horseback work for fifty years. Many a year passed that I never missed a day bein’ in the saddle. I stayed thirteen years on one ranch…I know when we used to camp out in the winter time we would have these old-time freezes, when ever’thing was covered in ice. We would have a big, fat cow hangin’ up and we would slice that meat off and have the best meals. And when we was on the cow hunts we would start out with meal, salt and coffee and carry the beddin’ for six or eight men on two horses and carry our rations on another horse…. When we camped and killed a yearlin’ the leaf fat and liver was one of the first things we would cook. When they would start in to gather cattle to send to Kansas, they would ride out in the herd and pick out a fat calf, and they would get the ‘fleece’ and liver and broil the ribs. The meat that was cut off the ribs was called the fleece.” Young African American cowboy standing by his horse

Cased tintype

Cased tintype

Cowboy wearing leather chaps and kid gloves and holding a bullwhip

Unknown photographer, ca. 1890

2003.109

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

The bull whip was a long woven whip attached to a handle of hickory or white ash. At the butt each lash formed a loop and was frequently more than 1 inch thick. The lashes were from 18 inches to more than 10 feet in length and graduated in thickness to the tip. Many riders might use while trailing cattle. In the hands of an expert one rider could do as much work as two riders without whips. Philip Ashton Rollins in The Cowboywrites, “It could, at the wielder’s choice, land anywhere, silently or with a pistol crack, and this with either the gentleness of a falling leaf or force sufficient to remove four square inches of…skin.”

Rollins in The Cowboy enumerates various cowboy titles: “The cowboy was not always called ‘cowboy.’ He everywhere was equally well known as ‘cowpuncher’ or ‘puncher,’ ‘punching’ being the accepted term for the herding of live stock. In Oregon he frequently was called ‘baquero,’ ‘buckaroo,’ ‘buckhara,’ or ‘buckayro,’ each a perversion of either the Spanish vaquero,’ or the Spanish ‘boyero,’ and each subject to be contracted into ‘bucker.’ In Wyoming he preferred to be styled a ‘rider.’ To these various legitimate titles, conscious slang added ‘bronco peeler,’ ‘bronco twister,’ and ‘bronco buster.'”

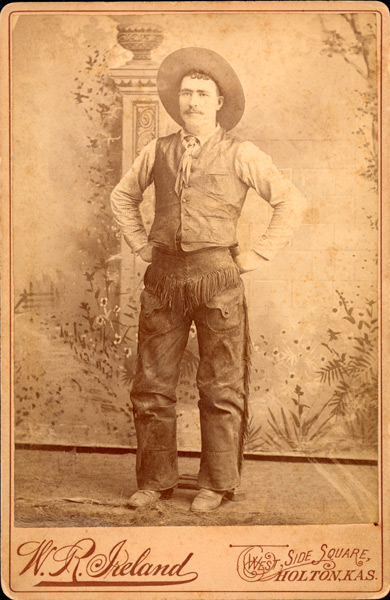

Tintype

Tintype

S. Griggs, Kansas cowboy

Unknown photographer, ca. 1880

2003.117

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

S. Griggs was in his 20’s when this photograph was taken. Among the items he wears are leather chaps and a “Mexican Loop” pattern holster with a plain cartridge belt with 3 integral loops securing the body to the skirt. Griggs later moved to Pike County (perhaps Griggsville), Illinois where he was a farmer. Named for Zebulon M. Pike, Pike County was formed on January 31, 1821. Griggsville was laid out in 1833 by Joshua R. Stanford, Nathan W. Jones, and Richard Griggs and named in honor of Griggs. Griggsville was organized in 1850.

An article in the February 27, 1887 Democratic Leader in Cheyenne, Wyoming reads: “The cowboys of the far West have a language of their own which no ‘tenderfoot’ may attain until he has served his novitiate. They call a horse herder a ‘horse wrangler,’ and a horse breaker a ‘bronco buster.’ Their steed is often a ‘cayuse,’ and to dress well is to ‘rag proper.’ When a cowboy goes out on the prairie he ‘hits the flat.’ Whiskey is ‘family disturbance,’ and to eat is to ‘chew.’ His hat is a ‘cady,’ his whip a ‘quirt,’ his rubber coat a ‘slicker,’ his leather overalls are ‘chaps’ or ‘chapperals,’ and his revolver is a ’45.’ Bacon is ‘overland trout’ and unbranded cattle are ‘mavericks.'”

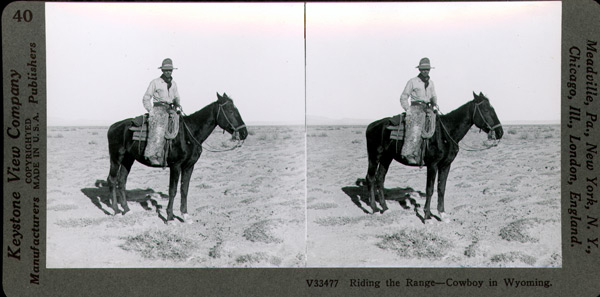

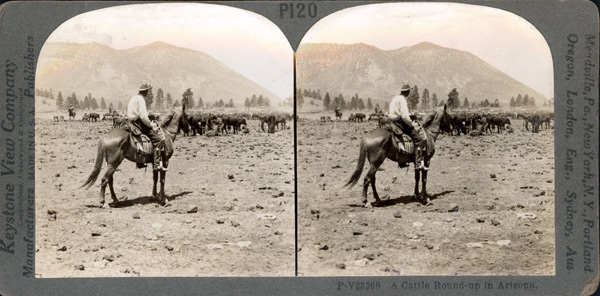

Stereograph

Stereograph

A Cattle Round-up in Arizona

Keystone View Company, Meadville, Pennsylvania, 1934 [ca. 1890]

2003.130

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

“Bill Nye on Cowboys,” an article in the February 18, 1888 issue of theSan Marcial Reporter in San Marcial, New Mexico reads: “The genuine cowboy is not always beautiful, but he is conversant with his business, knows every brand in his district at least and who owns it, is brave where bravery is most needed, that is in the discharge of his duty. To stand watch all night in a blizzard and hold a band of restless, bellowing cattle from stampeding, to ride all the next day half asleep in his saddle, to fall occasionally from his pony when the latter makes a mistake and steps into a prairie dog village, or to have a collar bone broken when fifty miles from a physician, are some of the features of cowboy life which the boys who run away from school to cross the Missouri do not know.”

In a December 14, 2003 article entitled “America: Rogue State?: An essay on our coming war…” at wastedirony.com the unidentified author writes, “The problem with America as a rogue gunman, sorry, lone gunman, is that we can’t do it alone. American leaders were smart enough after World War II to realize (mostly) that international agreements were necessary to keep the peace and prevent the spread of nuclear weapons. Bush and his cabinet have forgotten this. The more we act like a cowboy, the more the rest of the world is going to want to get a pair of six-guns as well.”

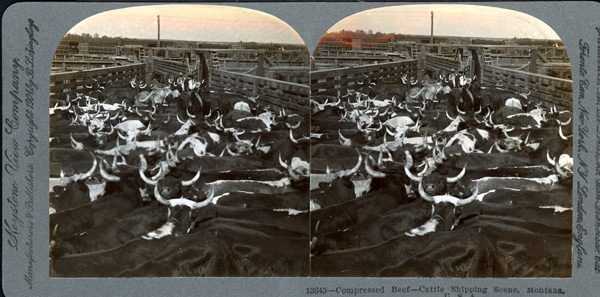

Stereograph

Stereograph

Compressed Beef – Cattle shipping scene, Montana, U.S.A.

Keystone View Company, Meadville, Pennsylvania, 1904

2003.136

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

J’Nell L. Pate describes a typical routine of a “Stockyards Cowboy” in the 2000 book, The Cowboy Way, edited by Paul H. Carlson. At a stockyards sometimes hundreds of workers were employed “to unload animals from railroad cars, drive them to pens, feed and water them, and clean up the pens. Folks working for any of such businesses were simply called ‘yard hands.’ Other livestock workers included muleskinners or wranglers who worked with the horses and mules, cattle raisers’ brand inspectors, men dipping animals for ticks…, veterinarians…, weighmasters, telegraph operators, and reporters for livestock market newspapers.”

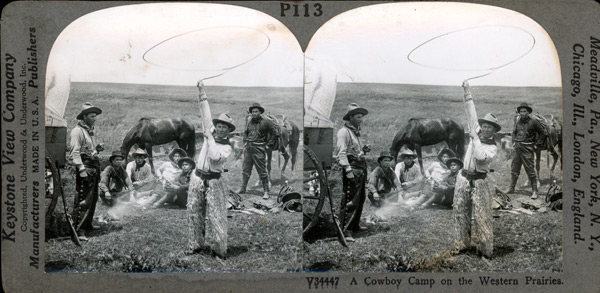

Stereograph

Stereograph

A Cowboy Camp on the Western Prairies

Keystone View Company, Meadville, Pennsylvania, 1934 [ca. 1890]

2003.137

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

Giles Fraser in his article “Never Trust a Christian Cowboy: To rally support for war on Iraq, George Bush presents himself as both lone ranger and good samaritan,” published on October 23, 2002 by the Guardian/UK, wrote, “The cowboy represents a popular point of reference in American culture and has been drawn upon by successive US politicians to justify both domestic and foreign policy…Likewise, war itself is often viewed through the prism of the movie cowboy mythology. Here is the plot of an archetypal western movie: the hero comes to town, though the community does not fully accept him. Some evil threatens to overwhelm the town. Initially, the hero tries to avoid getting involved. However, after exercising much restraint and so as to protect the community, the hero is forced to square up to the villains. Gun in hand, and at considerable personal risk, the hero kills the villains and makes the town safe. The hero leaves town. This is the paradigm against which war against Saddam is being considered. From Bush’s perspective, the resistance of the international community to the war on Iraq is therefore to be expected – it’s part of the script. So too, perhaps, is Bush’s notorious inarticulacy. For the cowboy is essentially a man of action, not talk. The image of the lone gunfighter who is suspicious of fancy talk and who acts fearlessly to defeat the forces of evil is the defining mark of a certain sort of US national pride.”

Vickie C. on September 22, 1999 posted text about a vision she had on write-the-vision.net entitled, “Jesus is a cowboy?!!!” She wrote in part, “I saw Jesus standing, very tall of stature He was, in front of the sanctuary, (right in front of the piano)…Jesus was swinging over His head a large rope lasso or lariat, just like a cowboy!…and very expertly too. I saw it was a red rope. Suddenly, He threw His rope/lariat over the congregation….a person reached their arms up and grabbed His rope, and He had this one ‘caught’ then…”

Stereograph

Stereograph

Among the 30,000 cattle at Sierra Bonita Ranch – roping a yearling, Arizona

Underwood & Underwood, New York, New York, ca. 1900

2003.142

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

Darrell Arnold in his article “The Cowboy Image” on www.cowboymagazine.com, Summer 2000, writes, “The man on horseback has, throughout history, stood literally and figuratively above other men. It is the horse that has made that so. Indeed, ranchers contend that one of the reasons they continue to try to struggle on in the cow business is because it gives them the opportunity to get horseback as often as possible. The horse is an extension of the true cowboy. The authentic cowboy does not exist if he is not capable of performing the working cowboy’s horseback tasks. If he’s not horseback, a man who works cows is just a farmer.”

Photographic postcard

Photographic postcard

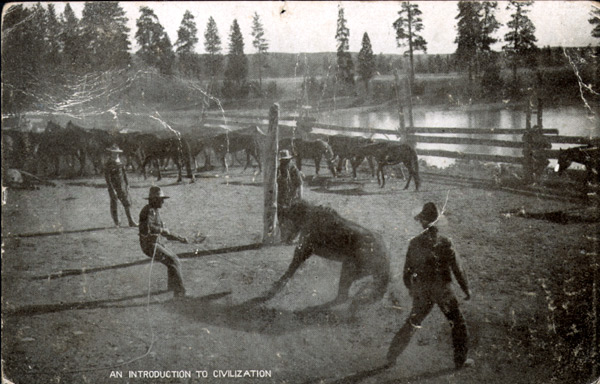

An Introduction to Civilization

W. T. Ridgley Calendar Co., Great Falls, Montana, 1907

2003.144

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

Will James in his 1925 book, Cowboys North and South, writes about the makings of a cow-horse. “A month or so before the round-up wagons pull out, the raw bronc (unbroke range horse) is enjoying a free life with the ‘stock horses’ (brood mares and colts)….He’s cut out with a few more of his age and put into a small round corral – a snubbing post is in the centre – and showed where, according to the rope marks around it, many such a bronc as him realized what they was on this earth for. The big corral gate squeaks open and in walks the long lanky cowboy packing two ropes; one of them ropes sneaks up and snares him by the front feet just when he’s making a grand rush to get away from it. He’s flattened to the ground and that other rope does the work tying him down. A hackamore is slipped on his head while the bronc is still wondering what’s happened, and from the time he’s let up for a sniff at the saddle he’s being eddicated….”

The Denver Daily Times in its July 19, 1872 issue asks the question, “Have you ever seen the boys at work breaking broncos? If you have not, a fiendish delight is in store for you. Get out on some ranch where a half dozen of this sweet breed of equines are undergoing this process. They take to it kindly – and they will take to you, if you happen to get within striking distance of their fore or hind legs. They have excellent teeth, too, as a ‘torn, but flying,’ pair of pants in our groaning wardrobe, sadly attest. And then, after a bronco, is ‘well-broken,’ and you buy him and take him home, he reminds you, in a variety of delightful ways, that he has not forgotten – will never forget – his natural instincts.”

Carte de Visite

Carte de Visite

Finely dressed Montana man wearing long coat and hat

Unknown photographer, ca. 1890

2003.163

Purchase by Donald C. & Elizabeth M. Dickinson Research Center

In his Dallas Morning News article, “Lost in Translation: When It comes to cowboys, it’s time to set outsiders straight on movies, politics and the real thing,” posted on www.philly.com on March 14, 2003 writes, “The yammering class in Europe – politicians, journalists, pundits and the like – lately has taken to referring to President Bush as a ‘cowboy’…When these people say Bush is a ‘cowboy,’ they aren’t being nice. They say he’s a ‘bellicose cowboy.’ They mutter about ‘cowboy-style unilateral action’…The ‘cowboys’ these folks have in mind are from old movies…But Europe’s favorite movie ‘cowboy’ is John Wayne. The Duke. And it’s the Duke who most often makes veins pop out on European foreheads whenever the president appears on television.”

Carla Marinucci and John Wildermuth report in their September 24, 2002 San Francisco Chronicle article, “Gore Blasts Bush’s ‘cowboy’ Iraq policy,” that Al Gore said, “‘after Sept. 11, we had enormous sympathy, goodwill and support around the world’…Gore later told reporters the Bush administration had been guilty of a ‘do-it-alone, cowboy-type reaction to foreign affairs,’ saying ‘there’s ample basis for taking off after Saddam, but before you ride out after Jesse James, you ought to put the posse together.'”