Welcome to the blog about our podcast “This Week in the West.” Each week, we’ll share the show’s scripts here on our blog. If you want to listen, click above, subscribe on your favorite podcast app or check back here every Monday.

If you have questions, ideas or feedback about the podcast, you can reach out to podcast@nationalcowboymuseum.org

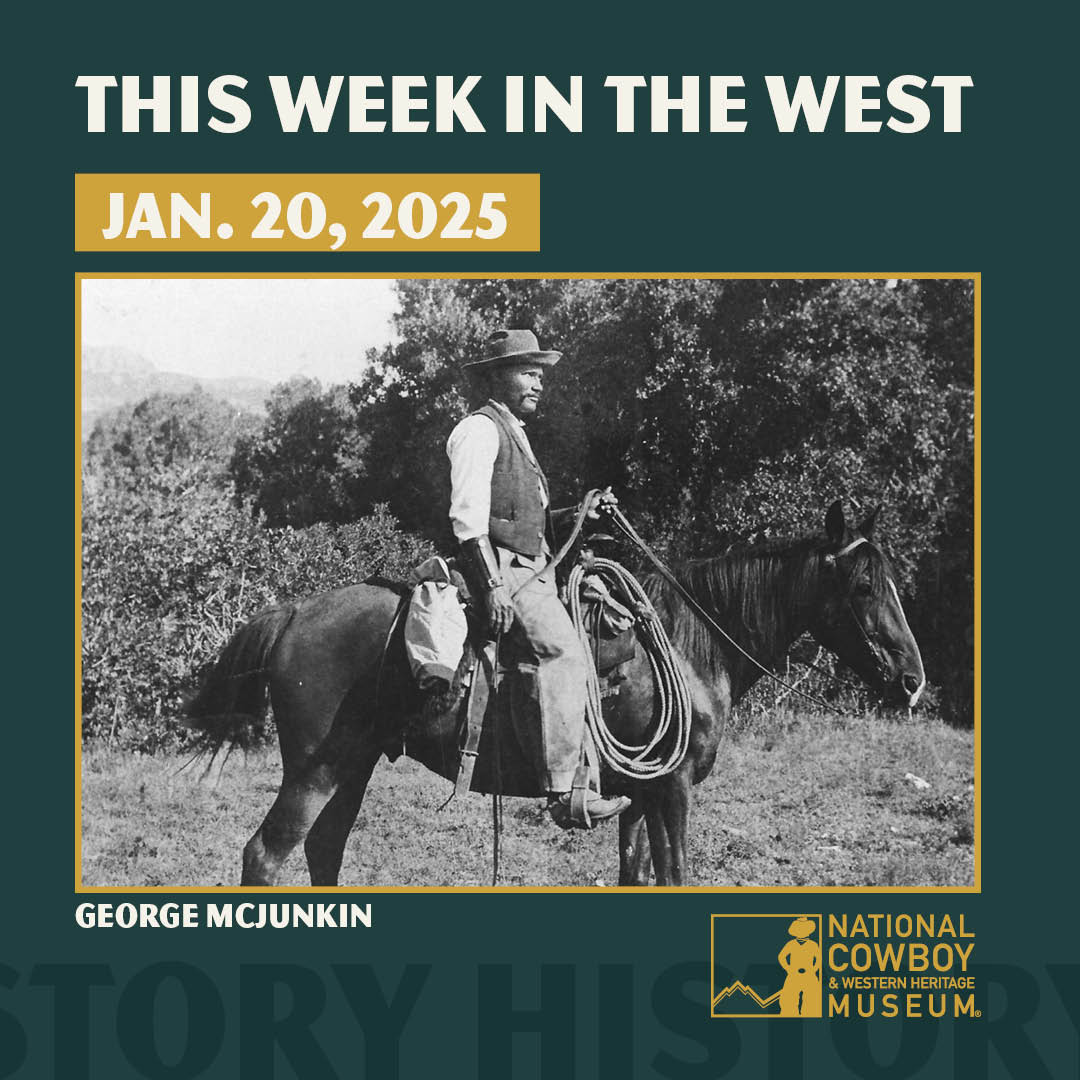

Episode 12: George McJunkin

Howdy folks, it’s the third week of January 2025 and welcome to This Week in The West.

I’m Seth Spillman, broadcasting from the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City.

On this podcast, we share stories of the people and events that shaped the history, art and culture of the American West—and those still shaping it today.

George McJunkin stood at the summit of the Capulin Volcano in northern New Mexico and looked over the valley below. He had long since left his boyhood in slavery; he had made his own way. He was a Cowboy.

To his west were the Sangre de Christo Mountains and spreading out in the valley below the volcano was the land that had become his home: The Dry Cimarron. He called it his “Promised Land.”

What he would discover in the earth beneath him would create a legacy for the cowboy and rewrite the history of the continent. We remember McJunkin this week, the anniversary of his death, January 21, 1922.

All McJunkin ever wanted to be was a cowboy.

McJunkin was born into slavery in 1851 on a ranch in central Texas, where his father was a blacksmith. His father eventually bought his own freedom, but by the time he had saved up to buy George’s, the Civil War had ended, and the enslaved people in Texas were emancipated.

McJunkin had been fascinated by the cowboys and Mexican vaqueros who rode past the ranch, driving cattle. He sought them out to learn about horsemanship, roping and wrangling. He stayed on at the ranch after the war for a few years, but by 17, he had joined his cowboy heroes on the cattle trails, crisscrossing the Southwest.

He traveled to the Santa Fe Trail into New Mexico, earning the reputation as a skilled hand. Along the way, a friendly family taught McJunkin how to read.

Once kindled, McJunkin was possessed by a fire to learn as much as he could. He taught himself to speak Spanish and play the violin. But it was the natural sciences that held McJunkin’s focus. He collected minerals, fossils and bones from his travels and eventually kept them on a shelf in the cabin he built near Folsom, New Mexico.

It was near Folsom where McJunkin was hired to be the foreman at the Crowfoot Ranch, an accomplishment for any African American in the postwar years.

McJunkin was still there on August 27, 1908, when a storm rolled in, dumping 14 inches of rain on the Dry Cimarron. Flash floods hit the settlers in Folsom, killing 17 people.

When McJunkin went out after the flood to inspect the damage, he noticed that part of the Wild Horse Arroyo, a nearby gully, had been washed away.

Uncovered were huge bones and stone-age tools. Although McJunkin was only self-taught in science and natural history, he knew he’d found something special. The bones were down too deep and were too big to be modern buffalo. He also found pieces of flint, seemingly worked by human hands. These bones, he thought, must be incredibly old.

McJunkin knew his discovery was important, but he could not catch the interest of archeologists. He spent years trying to get attention from any scientist he could.

In 1918, he sent some of the bones to the Denver Museum of Natural History. They dispatched a paleontologist to the site, but he only did some exploratory digging.

George McJunkin died in 1922.

Four years later, in 1926, a group of scientists, including that Denver paleontologist, returned to the Folsom site and did a full excavation around what McJunkin had discovered.

The bones were from Giant Bison, a long-horned species that stood over seven feet tall and weighed nearly 3,000 pounds. They had gone extinct at the end of the last Ice Age. The tools surrounding the bones were spear points that had been used to kill them, 32 bison in all, in the areas surrounding McJunkin’s find.

The Folsom fossils sent shockwaves through the archeological world. The tools were thought to date back to 10,000 BC, which radically changed the contemporary understanding of when ancient people first came to North America.

George McJunkin’s legacy was a literal rewriting of history.

Fortunately, McJunkin’s role in finding the Folsom fossils was not lost to history. He’s remembered not just as a self-taught cowboy but as an extraordinary amateur archeologist.

In 1961, Folsom was named a National Historic Site. In 2019, McJunkin was inducted into our Hall of Great Westerners.

And with that, we’ve dug up the end of another episode of “This Week in The West.”

Our show is produced by Chase Spivey and written by Mike Koehler

Follow us and rate us on Apple podcasts or wherever you hear us. That helps us reach more people.

We can follow us on social media and online at nationalcowboymuseum.org.

Got a question or a suggestion? Drop us an email at podcast@nationalcowboymuseum.org

We leave you today with some words from University of Houston historian Catherine Patterson, who has studied George McJunkin’s legacy: “Scientific discovery can be a messy process. Experts often cling to ideas that turn out to be wrong, while new discoveries are ignored. What a shame this ex-slave cowboy amateur never knew that his explanation of those old bones would trump the world’s experts.”

Much obliged for listening, and remember, come Find Your West at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.