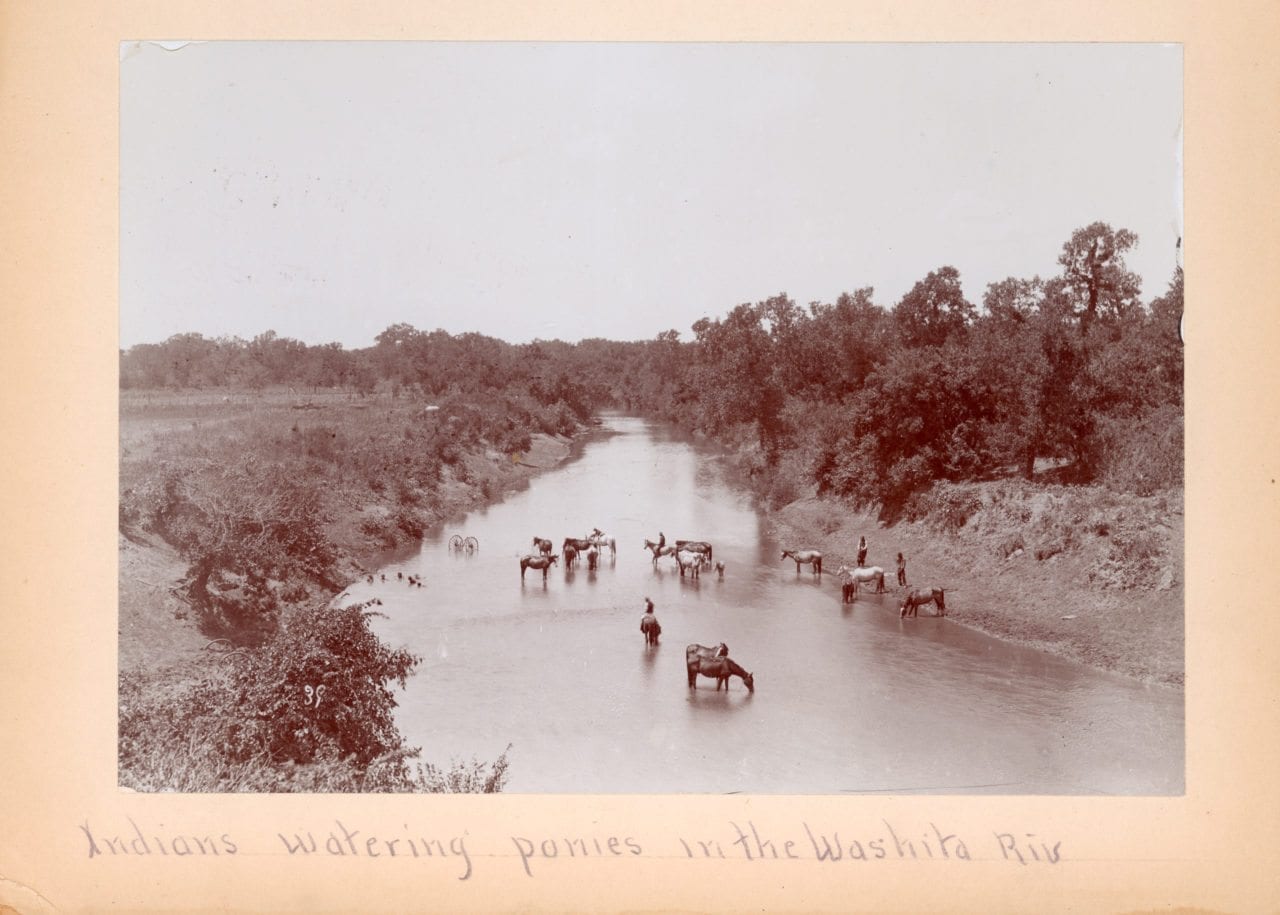

Indians Watering Ponies in the Washita River, ca. 1899, photography by William E. Irwin, courtesy Dickinson Research Center

Kenneth Riley’s Prix de West-winning painting evokes an infamous clash between George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry and Chief Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyenne.

Sundog, (1995) by Kenneth Riley, Oil on canvas, 48” x 42”, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum Prix de West Collection

Featured within the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum’s Robert L. and Grace F. Eldridge Gallery are works that have won the prestigious Prix de West Purchase Award. These collected pieces are some of the most stunning examples of Western American art found anywhere in the world.

Yet among this rarified air one work stands apart: Sundog, Kenneth Riley’s 1995 Purchase Award painting.

While most all of the Prix de West winners exhibit a realism that sets them in a respective location or period, Sundog foregoes concrete detail to convey its world instead through a style that National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum Assistant Director Mike Leslie describes as “impressionistic.”

“The two men in the painting are not placed into some sort of ‘historical or cultural context’ like you see with (Prix de West Purchase Award recipients) Martin Grelle, Howard Terpning, and others,” Leslie said. “It has a much more loose interpretation about it, soft edges, and not overly defined.”

In a March 2003 interview that accompanied a retrospective of his work at the Museum, Riley, who died in 2015, said that Sundog is his attempt to capture the “philosophy of the Native American people, and how the various phases of the sun’s rising and descent might have affected them. …”

“The Native people seeing this transformation taking place in the sky, with this awesome display of the multiple suns, it was probably a rather awe-inspiring event for them,” Riley said.

Yet aside from this impressionistic rendering of two Plains Indian warriors reacting to a mythology-laden solar occurrence, what exactly does Riley’s painting signify?

When one considers that the appearance of sundogs actually presaged the Battle of the Washita, it becomes clear how an abstract work of art, when viewed through a certain contextual prism, can reveal a story as profound as that of the United States’ conflict with Plains Indian cultures of the 19th century.

Early on the morning of November 23, 1868, the 7th Cavalry struck south from the newly established Camp Supply, in present-day northwest Oklahoma. Their orders were to make a sweeping arc south to the valley of the Washita River then east toward Fort Cobb, searching for fresh sign of any war parties returning from Kansas. Should an encampment of “hostile” Indians be found, they were to engage them.

By November 26, the column had the Antelope Hills – rising 300 feet above the surrounding plains – in sight. As no tracks signifying Indian activity had yet been encountered, Lt. Col. George Custer ordered Major Joel Elliott to take three companies of men on a scouting expedition up the Canadian River.

While the main body of cavalry and wagon teams began to ford the ice-choked Canadian River, Custer and a group of officers ascended the Antelope Hills. Upon reaching the top, they witnessed a spectacular sight.

“Suddenly we were enveloped in a cloud of frozen mist,” Lt. Edward Godfrey would later describe. “Looking at the sun we were astonished to see it surrounded by three ellipses with rainbow tints, the axes marked by sundogs, except the lower part of the third or outer ellipse which seemingly was below the horizon, [revealing] eleven sundogs. This phenomenon was not visible to those on the plain below.”

While still atop the Antelope Hills, Custer spotted a runner approaching — Elliott had sent word that a fresh trail of approximately 150 warriors had been found. Custer ordered his troops to advance quickly. Late that night, Custer’s scouts confirmed the location of Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle’s village. Before dawn, the 7th Cavalry had the village surrounded.

When what’s known today as the Battle of the Washita ended, anywhere from a dozen to 150 Southern Cheyennes were killed (estimates vary greatly), including Chief Black Kettle — long a proponent of peace with the United States — and his wife, whose bodies were left floating in the icy waters of the Washita. Black Kettle’s village and most possessions within it were destroyed, along with nearly 700 ponies.

The 7th Cavalry lost 21 men killed, including a group of 18 who had rushed off in pursuit of fleeing Indians, only to be surrounded and killed to a man.

The leader of this slaughtered detachment? Major Joel Elliott, whose scouting assignment the previous day had kept him from accompanying the other officers to the top of the Antelope Hills where the sundogs were witnessed.

For more information on the Battle of the Washita, visit https://www.nps.gov/articles/washita.htm